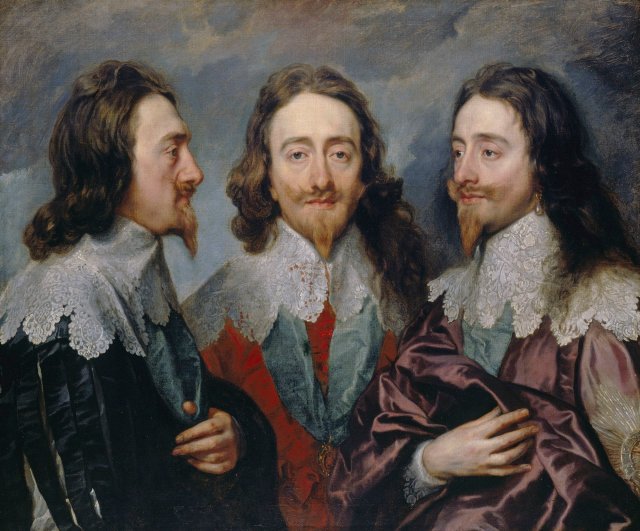

ANTON VAN DYCK (1599-1641)

Triple portrait of Charles I (1635-36)

Oil on canvas (84.5 x 99.5 cm)

Royal Collection, Windsor Castle

(To enlarge the picture, right-click on it and choose “Open in a new tab”)

The painting was probably begun in the second half of 1635. In his letter to Lorenzo Bernini of 17 March 1636 the King expressed the hope that Bernini would execute ‘il Nostro Ritratto in Marmo, sopra quello che in un Quadro vi manderemo subito’ (‘Our Portrait in Marble, after the painted portrait which we shall send to you immediately’). The bust was to be a papal present to Henrietta Maria, and Urban VIII had specially arranged its creation at a time when hopes were entertained in Rome that the King might lead England back into the Roman Catholic fold.

The bust was executed in the summer of 1636 and presented to the King and Queen at Oatlands on 17 July 1637. It was enthusiastically received by them, and their court and universally admired “not only for the exquisiteness of the work but the likeness and neat resemblance it had to the King’s countenance” as the English sculptor Nicholas Stone wrote. Bernini was rewarded in 1638 with a diamond ring valued at £800. Unfortunately, the bust was destroyed in the fire at Whitehall Palace in 1698.

One of the main attributes of a portrait painter is his skill to penetrate beneath the surface and reveal hidden aspects of the sitter’s personality. Van Dyck was undoubtedly gifted in that regard, but he was also a consummate courtier. Therefore his portrayal of the King is not as revealing as Christopher Lloyd claims in “The Royal Collection” (London, 1992). According to the English art historian:

“Here, therefore, the viewer is aware of Charles I’s elegance, refinement, sensitivity, intelligence, dignity and shyness; but also of his single-mindedness, obtuseness, aloofness, stubbornness and the surprising mental and physical strength that was to be so severely tested during the Civil War.”

It is surprising that such a knowledgeable man could have expressed himself so foolishly. Some things are impossible to convey in a portrait, such as shyness, aloofness, stubbornness and particularly mental strength. It seems that Lloyd felt the necessity to say something when there was no need for that. As the saying goes “a picture is worth a thousand words.”

Van Dyck’s portrait shows a man of melancholic nature, the consequence of a sad, lonely, uneasy childhood and adolescence. Charles grew into an aloof, diffident and defensive man. Although lacking in confidence, Charles was acutely aware of the responsibilities of his office and made himself play to the full what he regarded as the proper role of a king. Yet within a few years of his accession to the throne in 1625, he had transformed himself into a dignified, kingly figure every bit as impressive as his counterparts on the continent. This transformation came about partly through an effort of willpower and self-control. Van Dyck was the perfect portrait painter for a man like Charles I, he endowed him with an air of serene self-possession and inner confidence which was regarded as the essence of true nobility.