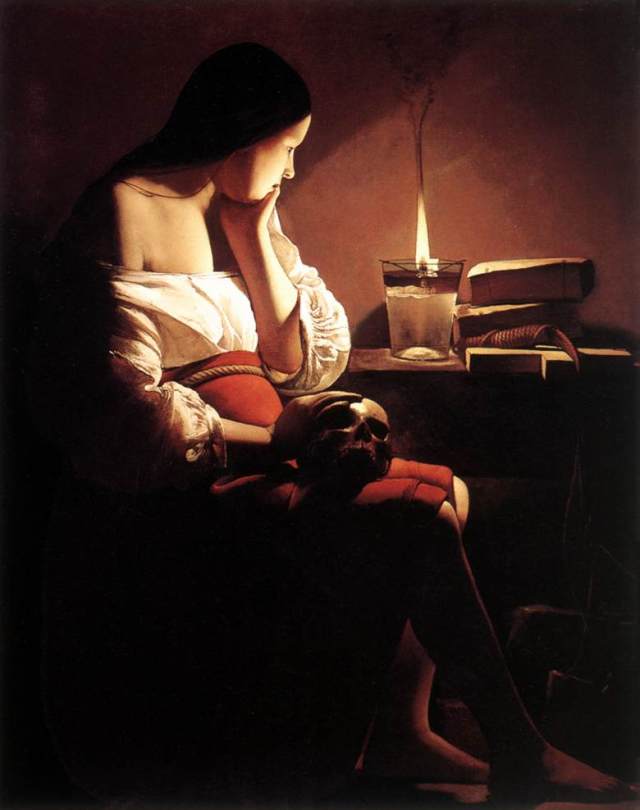

GEORGES DE LA TOUR (1593-1652)

The Penitent Magdalen with the Smoking Flame (c.1638-40)

Oil on canvas (117 x 92 cm)

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

To enlarge the picture, right-click on it and “Open in a new tab”

Georges de La Tour was the greatest tenebrist painter working in 17th-century France. Indeed since his “rediscovery” early in the 20th century, he is ranked second only to Caravaggio, the Lombard artist who invented tenebrism in Rome at the beginning of the 17th century. Basically, it consisted of genre scenes dramatically illuminated against a dark, almost black, background; the figures were not idealized, beautiful bodies, but portraits of common folk, taken (as Caravaggio said) “from of the streets”.

In a previous post (see: The Musician’s Brawl) I discussed the probability that de La Tour may have had the chance of visiting Utrecht around 1616, but there is no documentary evidence of it. It is tempting to believe it so since de La Tour’s style of chiaroscuro (1) owes more to Gerrit Honthorst and Hendrick ter Brugghen than Caravaggio. Like the Dutchmen de La Tour built up his nightly scenes around soft candlelight instead of illuminating the characters with a harsh light coming from the left. There is a general consensus among scholars that in the mid1630s de La Tour developed his own celebrated tenebrist manner. This is long after he was likely to have been exposed to any direct experience of Caravaggio or any of his followers.

The following lines are excerpts of the essay written by Philip Conisbee (1946-2008) for the catalogue of the exhibition “The Ahmanson Gifts” organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) in 1991.

“The Penitent Magdalen with the Smoking Flame is one of the artist’s finest nocturnal scenes. It depicts a subject that was especially popular in Catholic Europe during the Counter-Reformation in the 17th century. If Protestant reformers decried both the Catholic adoration of saints and the use of images as a stimulus to piety, the Catholic Church responded by asserting both traditions even more firmly. Images of the penitent Magdalen were particularly favoured because she appealed to both rich and poor alike in her rejection of the blandishments of the material world in favour of the spiritual life as a follower of Christ. Her apocryphal story is told in Jacobus de Voragine’s compendium of the saints’ lives, The Golden Legend, compiled in the 13th century and still the standard source for her life in the seventeenth century.

De La Tour shows Magdalen in her retreat from the world, as she sits alone in a dark and austere interior. She is no longer dressed in her elaborate and elegant courtesan costume but wears plain, homespun clothes, her skirt supported by a simple cord. Her hair is undressed and her feet are bare in humility. On the table is a knotted scourge used in the mortification of the flesh, a plain wooden cross and two books. On her lap, she cradles a skull, a symbol of the inevitable mortality of the flesh. Mary’s attention is concentrated above all on the steady glow of the flame rising from the simple oil lamp on the table. The light has a mystical significance, it represents Truth and religious Faith. The artist has chosen not to stress her penance or her devotion to prayer; he rather emphasizes her spiritual enlightenment. Voragine wrote that the Magdalen was to be interpreted as “a light giver”. More than penance or heavenly glory she chose the way of inward contemplation and became “enlightened with the light of perfect knowledge in her mind”

De La Tour brilliantly deploys the light of the oil lamp to simplify his composition, eliminates the irrelevant detail and directs attention to the most meaningful features of the painting. For all the simplicity of its subject matter is a very beautiful work. The softness of the light creates an almost palpable atmosphere, and the artist has taken a great deal of care in describing the different surfaces it reveals: the smooth, plump flesh of the young Magdalen, the creamy white of her blouse, the deep red of her skirt, the various gleams given off by the surfaces of bone, vellum and glass. This very high level of aesthetic accomplishment plays an important part in engaging the spectator’s attention and also suggests something of the spiritual rapture being experienced by Magdalen as she reflects on what it means to follow Christ.”

(1) Chiaroscuro is an Italian word that literally means “light-dark”; it was employed to describe Caravaggio’s technique that consisted in brutal contrasts of light and drakness, hence also the expression “tenebrism” that derives from the Italian tenebroso (dark) which comes from the Latin tenebrosus (dark, gloomy)