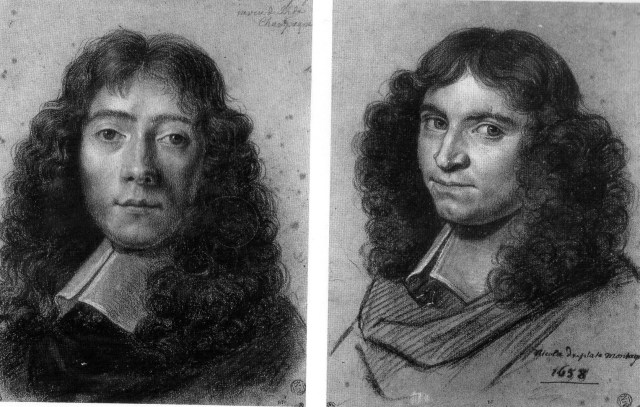

JEAN BAPTISTE DE CHAMPAIGNE (1631-1681)

NICOLAS DE PLATTEMONTAGNE (1631-1706)

Double portrait of the artists (1654)

Oil on canvas 132 x 185 cm

Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam

To enlarge the picture, right-click on it and “Open in a new tab”

The drawing board on the left announces that Nicolas de Plattemontagne painted the portrait, presumably referring to the one of Jean-Baptiste de Champagne, while the inscription on the easel credits it to Jean-Baptiste de Champaigne, which must therefore mean the portrait of Nicolas de Plattemontagne. Both are very similar to the two drawings at the Louvre. The drawings seem to have been made independently of the painting rather than as studies for it

An inscription on the drawing of Jean-Baptiste identifies him as the nephew of the distinguished painter Philippe de Champaigne. He moved to Paris at the age of thirteen and presumably met Nicolas through his uncle, as Nicolas, who was born in Paris, studied with Philippe de Champaigne.

The signatures on the canvas thus confirm that Nicolas painted the portrait of Jean-Baptiste on the left and that Jean-Baptiste portrayed his friend Nicolas on the right. It is quite clear that the work is the product of two different hands. The figure on the left (Nicolas) has been rendered in cooler tones than the one on the right, the features of Nicolas are also sharper than Jean-Baptiste’s. The painters are shown in their studio surrounded by the tools of their trade: a drawing board, an easel, a palette with paint and another on the wall, and a shelf with plaster models, one of them a bust of Seneca.

The presence of the bust of Seneca deserves further elaboration. The Roman philosopher enjoyed an excellent reputation in the 16th and 17th centuries, this was partially due to the myth, born out of an outrageous fabrication known as “the correspondence between Seneca and St. Paul”, that Seneca converted to Christianity. The great English classical scholar and translator Edward Fairchild Watling ( 1899 – 1990) described Seneca´s reputation during the 16th century as that of “a sage admired and venerated as an oracle of moral, even of Christian edification; a master of literary style and a model [for] dramatic art.”

A significant addition to the objects that surround the artists is the viola-da-gamba that rests on Jean-Baptiste’s knee, he was obviously a music lover and an amateur musician.

A pleasing subject in its own right, this portrait is a superb example of the revival of classicism in French painting during the 17th century, a trend in which Philippe de Champaigne played an important role.